Chris Davis, Commercial Director for Kensa Heat Pumps explores the district ground source heat pump solution for flats, apartments and small private housing developments.

Specifying heating solutions for flats and apartments is becoming an increasingly complex affair. Once very much the domain of direct electric heating (due principally to its low capital investment cost), successive changes to Part L of the Building Regulations in recent years has meant specifiers now have to look for alternative, lower carbon options in order to meet building energy efficiency compliance requirements.

With many clients – both private developers and social landlords – often preferring to avoid the installation of individual gas boilers in each apartment of a multi-storey property on both safety and maintenance cost grounds, developers and housebuilders are beginning to consider alternative options such as heat pumps far more widely.

In particular, whole building ‘district heating’ systems are becoming more popular as developers look for simple, cost-effective solutions that help achieve compliance with building energy efficiency standards, while remaining cost-effective to install. Typically requiring a plant room and a central boiler or heat pump, distribution pipework circulates heat around the building, servicing Heat Interface Units at each apartment, which allow each resident to draw off heat or hot water for their dwelling as and when required.

Central plant

Unfortunately, this type of ‘central plant’ system is less than ideal for a number of reasons, even more so when heat pumps are the preferred heat generator. For example, heat losses in the distribution pipework lead to decreased efficiency and require an expensive oversized plant; summer over heating in common areas can be a problem (a result of these heat losses, as domestic hot water is needed all year round); heat pumps cannot be run at water temperatures where they are most efficient and cost-effective (35-55oC) when used with Heat Interface Units; and the provision of domestic hot water without a storage tank or separate high temperatures heat pump/distribution circuit is also a technical challenge.

Further complications come with the need to bill individual residents for their heat usage, requiring the administrative burden of metering, billing and recovering charges for each individual occupier’s heat and hot water consumption, now a legal requirement thanks to the Heat Network (Metering and Billing) regulations introduced in 2014.

There are thankfully however alternative options which developers and social landlords are beginning to adopt in the design of new buildings, centred on the specific benefits of ground source heat pumps.

Ground source heat pump

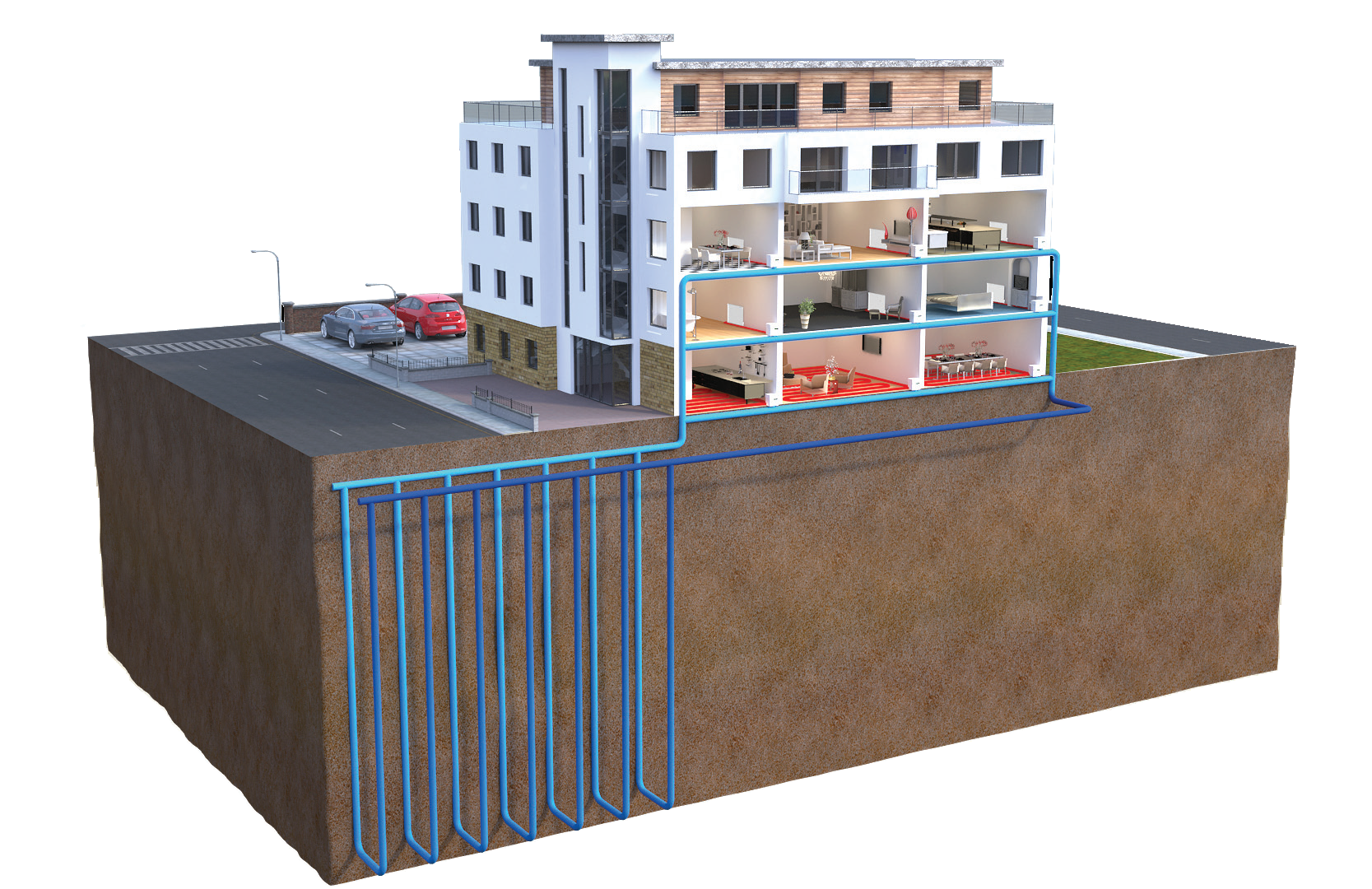

The solution has been pioneered by Kensa and sees the installation of small, ultra-quiet, ground source heat pump units within each property, linked in turn to a series of shared boreholes via low temperature distribution pipework around the building.

This has the benefit of providing each resident with their own heating appliance, which can be linked to the developers preference of radiators or underfloor heating, in exactly the same way as an individual gas boiler, but of course without the gas safety concerns or annual servicing requirements.

And because the water distributed around the building is on the ‘cold side’ of the heat pump, it is not subject to heat loss or any requirement to invest further in plant to overcome heat losses.

Own bills

Better still, each resident’s heat pump is connected to their personal electricity supply, meaning each settles their own bill directly with their preferred energy supplier and is perfectly able to switch suppliers as and when they see fit. This is in contrast to any heat supply contract which would otherwise be the case with a central plant heating system, where all residents are tied into the incumbent heat supplier.

Each home is furnished with its own ‘Shoebox’ ground source heat pump, a product which has been designed specifically to be small and quiet enough to be installed inside each apartment. Virtually silent in operation, the Shoebox fits in a single footprint below its own hot water cylinder, providing each resident with plentiful hot water and saving valuable space inside the property. And, of course, the opportunity to negate the need for any plantroom to house central heat pumps/boilers leaves the developer with more real estate available for sale.

Carbon savings

Ground source heat pumps are also able to exhibit significant CO2 savings over alternatives. Systems can easily be modelled in SAP and Target Emission Rates improvements of 40% or more are typical, enabling developers to easily meet carbon compliance objectives without the need for additional costly measures to satisfy with Building Regulations Part L requirements.

Crucially, this system architecture is classified as district heating and as such new build installations qualify for subsidy support via the Non-Domestic strand of the Government’s Renewable Heat Incentive (RHI) scheme. This subsidy support is appealing and means there is opportunity for the building management company to generate a long term income stream from the production of renewable heat.

Alternatively funders can provide the additional capital to cover the initial cost of the ground array, in return for allocation of the RHI funds, allowing the possibility for the ground array infrastructure to be owned and maintained by a separate entity, as is already commonplace with electricity and gas infrastructure for new build sites.

In short, this means that for no additional capital cost, the housebuilder is able to upgrade heating system specifications to ground source heat pumps and market a property with a superior SAP rating, lower running costs and low maintenance costs.

And while ideal for flats, this system approach does not have to be limited to multi-storey developments. The “shared ground array” approach can equally be applied to small private housing developments, with clusters of houses sharing ground collectors. This is ideal for developments that do not have easy or cost-effective access to the gas network, providing an alternative, highly viable heating solution to air source heat pumps or LPG.