Richard Fox, Principal Landscape Architect and Head of Services for Lockhart Garratt’s Oxfordshire office looks at the impact of Covid-19 on residential landscape design.

2020 may be behind us, but with a new lockdown initiated there appears to be little respite from the Coronavirus pandemic. It was a year of many challenges, and just 12 months ago, few could have predicted how lives would change as a result of Covid-19.

One of the most significant changes has been the shift to home-working and the dynamic of working patterns evolving to meet the challenges that we face. Many people now see home-working as the new normal, replacing the traditional nine to five and commute with a more balanced, fluid approach to both life and work. For some, this has meant a better work-life balance.

However, for others the challenge of home-working has been more difficult. For those without the space to facilitate home-working it’s meant that their homes, which prior to the pandemic served a single purpose, now have to fulfil multiple roles. Many lack the space to separate work and home life, meaning the traditional boundaries between the two have become increasingly blurred.

Appreciating the great outdoors

These internal changes have also had an external impact. The outdoors has become an essential escape for many, whether that be private gardens, public open spaces or the wider countryside. The increased focus and enjoyment of nature and the great outdoors is seen as one of the few positives to arise from the pandemic, creating an appreciation of natural assets such as fresh air, green spaces and exercise that was previously taken for granted.

However, the experience for those without a private outdoor space, or in urban locations where access to green space is reduced, is a very different one. The pandemic also highlights crucial social needs. As a species that thrives on physical and emotional connections to friends and family, the reality of lockdown and restrictions on movement emphasises the loss of these important social interactions.

Therefore, it’s unsurprising that the hardship of lockdown has been accompanied by a resurgence in a traditional sense of community. While I would argue that this has always been present, the need for community attachment and the desire to help and assist friends, family, neighbours and local businesses has once again been brought to the fore.

Meeting the new needs of the community

As designers, we need to adapt to and plan for the changing requirements of a post-Covid world. The traditional model of residential masterplanning which focused on density and return no longer allows for the creation of the kind of homes and spaces that people now want to inhabit.

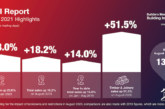

This is evidenced by a huge upsurge in the housing market, driven in part by the government’s Stamp Duty Land Tax holiday, but also by the desire to move out of densely populated urban settings in favour of more traditional suburban and rural locations where access to useable private gardens, public open spaces and the wider countryside is greater.

This means that landscape designers, planners and architects need to reconsider their approach to residential design, focusing on providing homes and places that allow people to incorporate the lifestyle changes that Covid triggered in 2020; and in turn to enhance society by creating homes and communities that have the capacity to accommodate change.

Green space at the heart of design

By creating developments where access to green space sits at the heart of the design ethos, we can create greener and more accessible places. As a landscape designer, I have long advocated the use of a landscape-led approach, where the provision and location of green infrastructure on site is at the heart of the design process – and in turns sets the framework for development on site.

By considering these factors at the outset, we achieve a much greater social and economic return from development. Furthermore, while development densities may be reduced as a result of this approach, there is value in providing homes that are not only liveable, but which meet the changed requirements of a post-Covid world.